The fight against cigarettes and climate change

There are striking similarities between cigarettes and oil. In the US, the battle against cigarettes throughout the 20th century gives an insight into the current and future management of our future with oil, gas, and climate change. Cigarettes harm individual people, while oil harms both the planet and individuals through pollution.

Cigarettes and oil are similar:

Each has positive, short term impacts but carry long term risks

Each are profitable businesses, which forms large business, lobbyist groups, and marketing and legal teams

Each has loyal customers who love the product and will justify their use. Any infringement on their use feels like an attack on personal liberty

Each industry has embedded the use in the culture

Each negatively impacts those in low income and developing nations/areas the hardest

Cigarettes have not always been popular; in 1900, cigarettes made up just 2% of the tobacco market. However, over the next half century, cigarettes gained in popularity and acceptance. Companies refined their product and marketing schemes to embed the product in the culture. They shot down questions of health and advertised to women and teens. By 1950, cigarette companies brought the proportion of smokers in the adult population to its peak at 46% of all American adults. Companies and regulators had little understanding of the long term impacts.

Oil had a similar beginning. Oil is a modern invention/discovery. For thousands of years we sat on top of oil with no use of it. Once the potential was recognized, the world changed forever. The magic of oil and the industrial revolution meant that oil was thrust into the world. Again, large oil companies extracted oil and fueled industrialization across the globe. We had no idea of the long term impacts to our planet.

Each product had a magnificent beginning. It was the ultimate symbol of modernity and influence. Gas powered vehicles operated by men smoking cigarettes - there was not a better image of American power in the 20th century. We loved them and got addicted to each.

With the addiction to cigarettes came the addiction to the cigarette money. For example, the first major tobacco company was the Tobacco Trust. In 1890 the Tobacco Trust had a market capitalization of $25 million. By 1910, the market capitalization grew to $350 million! The tobacco industry grew and protected its interests over the 20th century.

The oil industry saw the same gold mine. As the automobile became a household item, the industry began to touch every aspect of our lives. Without understanding long term risks, the oil industry became a force of power in business and politics.

The understanding of the negative implications of smoking and oil has come slow and not without significant push back. When science began to understand the dangers of smoking, the tobacco lobbyists sought to create a controversy around the dangers. They turned the evidence into a debate. With people in love with the product, it was difficult for science to make a compelling case against cigarettes. With each new study, the tobacco industry would claim “this doesn’t prove that it leads to lung cancer.”

At the beginning of the climate change fight, big oil actually sponsored some of the research around carbon emissions. However, when the evidence became clear of the danger to our environment, lobbyists worked to protect the oil industry. Again, a controversy was created around climate science. Our love for the convenience of oil and the progress it brought made it easy to hear any argument defending the industry.

Oil companies sought to make the oil industry an active participant in the scientific and policy debate. “It should highlight uncertainties in the sciences, question the effectiveness of any new regulations, urge international cooperation, and accept only those measures ‘consistent with broader economic goals,’ which is to say, actions that didn’t hurt profits.”

The scary truth of the cigarette battle was that the clear science of the harms to smokers did not catalyze the decline of cigarette use in the US. Rather, studies evidencing that secondhand smoke was harmful proved to be the only way to move the needle on smoking regulation.

A Japanese study released in the early 1980s found that, if a husband smoked a pack or more a day, the wife had a 90% greater chance of developing cancer than those whose husbands did not smoke at all.

When additional studies began to show the dangers of secondhand smoke, local governments and businesses began to pass laws and rules to limit smoking in public. These laws aimed to protect innocent nonsmokers.

This dismantled the cigarette industry’s personal liberty argument. Lobbyist loved the argument that smoking was an individual liberty and the government could not impede on one’s right to smoke. Once it became clear that smoking hurt others, the tobacco industry had nothing left to argue.

The fight for our planet will be similar to the fight for our nation’s health. It has been clear that climate change poses a risk to our planet for decades. As early as the 1950s, scientists began to understand the impact of carbon on the planet.

Nathaniel Rich explains in Losing Earth that in the late 1970s and 1980s there was real momentum to pass carbon legislation. The US saw itself as a leader of the world in reducing carbon emissions. There was bipartisan support to address carbon emissions and oil companies were putting money into global research research.

George H. W. Bush campaigned on passing legislation to combat the greenhouse effect. Following his victory, people believed legislation was inevitable. “The coal industry, which had the most to lose from restrictions on carbon emissions, had already moved beyond denial to acceptance.”

In 1989, over 60 countries joined in Noordwijk, a town in the Netherlands, to agree on a binding global agreement to freeze greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels. A Bush representative to the summit, John Sununu, played a major role in ensuring a resolution was not met. Sununu was a staunch convervative that doubted the scientific rigor of climate science.

“Sununu’s obstruction was critical, Reilly granted, at a time when there was little concerted opposition from any quarter, public support for climate policy was at an all time high, the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] process received vocal bipartical support, and a binding treaty along the terms broadly agreed on at Noordwijk would have kept planetary warming to 1.5 degrees.”

Following this resolution failure, the world has struggled to pass global binding climate agreements.

Just like cigarettes, the oil industry wants science to prove that oil is hurting the planet. We should put the burden of proof on the oil industry. Can Exxon executives say with absolute certainty that fossil fuels do not hurt the earth?

Like secondhand smoke, our argument must be to defend the rights of those who didn’t choose to pollute the world. We know climate change impacts the poor the most. We have to fight for the rights of all.

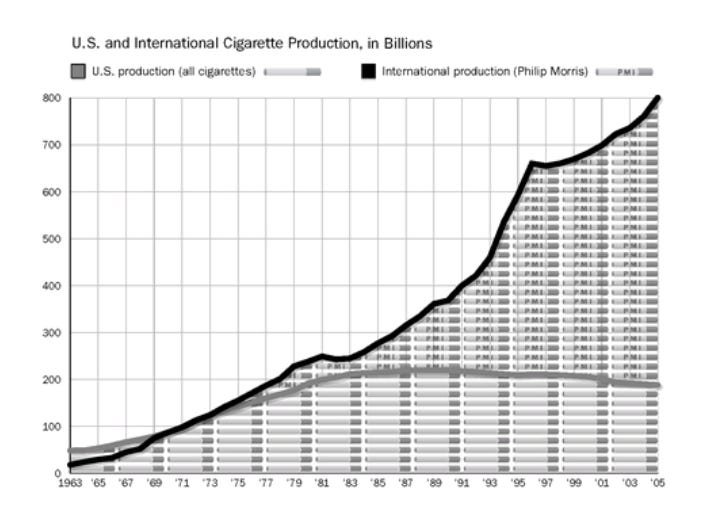

Cigarettes and oil hurt the poorest and most vulnerable the hardest. The cigarette industry continues to prosper because they have moved their influence to the emerging global markets. People in this market are less informed of the risks of smoking and smoking health effects tend to be of lesser concern given other risks. Nonetheless, cigarettes slowly kill people regardless of their global location. In addition, their governments are more relaxed on regulations against smoking. These markets are a second wind for US cigarette companies. The cost is millions of lives lost.

If we work harder to limit the power of cigarette companies in the developing world, we can improve the lives of more people than even eradicating the most gruesome diseases.

Once the cigarette companies realized that the US market was tapped and regulated, they moved global. The companies used their decades of marketing knowledge and experience to export a global health crisis.

“Of the world’s 1.1 billion current smokers, 80 percent live in low or middle-income countries with nearly 40 percent of the total number of smokers in the world living in East Asian countries and 20 percent living in former Soviet Bloc countries. By 2030, developing nations will claim 70 percent of the world’s overall tobacco mortality, exacerbating the health disparities between the developed and the developing world.”

The World Health Organization estimates that 200 million people will die of smoking related illness in 2030.

Oil derived pollution mirrors the global issue of cigarette smoking. Developing countries are exposed to pollution at a higher degree than those that can afford to move out of the city or pay to live in cleaner areas. Climate change will have devastating impacts on these less affluent communities.

Cigarettes and oil impacts are the result of the irresponsible export of risks from one group to another. Wealthy business leaders are able to enjoy the benefits of profitable addictive industries without ever experiencing the cost. They have unlimited upside with near zero downside risk. Oil and tobacco leaders will be retired and gone before the millions die from smoking and pollution.

This is central to Taleb’s argument in Skin in the Game. Taleb says that people should be responsible for the consequences of their actions. Large companies have first and second order effects of their decisions that impact people outside of their reach of consequence.

Taleb explains Skin in Game through Hummurabi’s code, “Hammurabi’s best known injunction is as follows: ‘If a builder builds a house and the house collapses and causes the death of the owner of the house – the builder shall be put to death.’”

While our morality has progressed since Hummurabi, the principle stands. People must be exposed to the same downside as those that they expose their risks.

People making large impactful decisions should be forced to have exposure to the downside risk. A tobacco executive demonstrates the absence of skin in the game in 1982:

“Demographically, the population explosion in many underdeveloped countries ensures a large potential market for cigarettes. Culturally, demand will increase with the continuing emancipation of women and the linkage in the minds of many consumers of smoking manufactured cigarettes with modernization, sophistication, wealth, and success—a connection encouraged by much of the advertising for cigarettes throughout the world. Politically, increased cigarette sales can bring benefits to the government of an underdeveloped country that are hard to resist.”

There are many many books and articles about how to solve the climate crisis. I will let others speak to this. However, helpful in understanding solutions to these problems stems from the ancients through the phrase “via negativa.”

Via negativa is addition by subtraction. Taking things out of a complex system that we know do not work is usually more helpful than adding more. Via negativa originates from Apophatic theology also known as negative theology. Apophatic theology aims to describe what God is not rather than describing what God is. Via negativa can be used to understand other complex systems.

Negative knowledge is more valuable than positive knowledge. The power of knowing something is not good is very difficult to reverse. For example, once we began to learn that smoking was bad for you, there was no reversing it. Negative knowledge built and built until we became more confident that smoking is bad.

The tobacco industry ingeniously flipped this on its head. Instead, they asked science to prove that smoking was harmful. In a complex system with many inputs like the human body, this is nearly impossible. Big tobacco framed the argument to the public as “there isn’t proof that cigarettes are bad, so keep buying our product.” Via negativa asks people to be conscious when adding something new to a complex system. The burden of proof is not on science to prove that smoking is bad. Rather, the burden of proof is on tobacco to prove that smoking cannot harm you.

Alas, hundreds of millions are already addicted to cigarettes. But, using via negativa, we can attempt to focus our global health initiatives on removing the bad rather than adding things with unknown consequences.

The Cigarette Century illustrates a product with invisible long term risks. A silent killer. I am not as passionate about climate change as many others, but I could not help to draw the comparisons.

The battle against big tobacco wasn’t just political. It required extensive scientific research. This was followed by a cultural shift. Following public persuasion, it required grassroots movements and local laws and business changes from all over the country. This was followed by additional major legislation and lawsuits. This brought us to today. The sad truth was that these changes helped the US but the problem went global.

The fight to combat climate change will mirror the fight against cigarettes in the US. As we are moving through the cultural shift phase, we will have to begin and continue to pass local and national regulations. However, we must be cautious of exporting another global crisis. We must learn from the global cigarette crisis and ensure that the world understands the impacts of climate change and the need for global action.