Pandemics: the risk, history, and response

Date of Publication: 2/12/20

Regardless of the novel coronavirus’s (COVID-19) ultimate impact, the idea of a global pandemic is concerning, and it is worth understanding the potential risks. The math, history, and government response applicable to this virus will be applicable for COVID-19 and the inevitable viruses to come.

I am hoping that this article will age poorly, and this will be labeled as an overreaction. However, I am operating under the precautionary principle: “a strategy for approaching issues of potential harm when extensive scientific knowledge on the matter is lacking.”

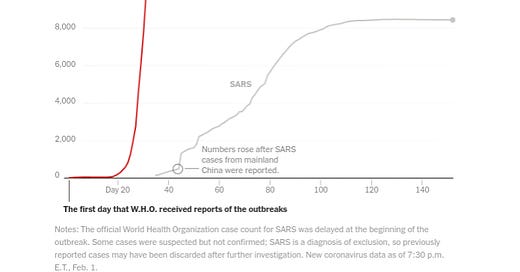

Viruses are particularly interesting because it is a real world example of the first lesson students learn when introduced to the power of exponents. Anything with exponential growth that lives in the world of power laws deserves attention due to its potential extraordinary impact. Graphs like the one below deserve specific attention. (Source: New York Times).

When some argue that deaths from car crashes is still larger than deaths from the coronavirus, they are missing the fundamental point of exponential impact.

With car crashes, we can predict the number of deaths per year within a reasonable margin of error. This is because one car crash is (mostly) independent from other car crashes.

With a virus, it is completely different. At this point in understanding the coronavirus, the range of potential casualties from the virus is virtually unknowable. It could be 2 thousand, or it could be 50 million. Because the virus spreads exponentially, the impact is potentially massive. With car crashes, there is essentially a 0 percent chance that there will be 50 million car crash deaths in a year. As such, viruses must be treated differently from other external threats.

This introduces the concept of R0 of a viral outbreak. R0 is a measure of how many additional people a case patient can infect. With initial studies showing an R0 of the new coronavirus to be between 2 and 3, this is a reason for huge concern (note we have no idea of the real number at this point). For discussion sake, we know it is certainly above 1.

As a comparison, the Spanish flu of 1918 was probably less than this at an R0 of 1.80. Living in a far more connected world, this outbreak has potential to touch every part of the globe. The R0 above 1 is especially frightening as it is self-sustaining. We would be living in a different world if the R0 was below 1:

“Many diseases exhibit subcritical transmission (i.e. 0 < R0 < 1) so that infections occur as self-limited ‘stuttering chains’.”

Containment efforts must be taken, but, unfortunately, one person who is missed by the containment will begin another exponential increase of the virus.

An important distinction of the the R0 number is, again, the distribution. R0 is the average number of additional people an infected person will infect. As such, there is potential that one person could infect far more than the average. For example, an infected person on a cruise ship has the potential to infect another 100 people. This idea is commonly referred to as the “super-spreader.”

It is concerning if the R0 of the novel coronavirus looks more like t3.

There is ample historical evidence to support caution around this viral risk - pandemics are not new to the world. Humans have suffered our entire existence from gruesome pandemics that have wiped out large numbers of the population. While optimists say "that kind of thing doesn't happen anymore," we should be cautious to use relatively mild recent viruses such as SARS or Ebola as a tool for comfort.

In just 1918, the Spanish flu killed 50 million people. While we have technology, improved medicine and hygiene, and instant communication on our side 100 years later, the world is more connected and more densely populated. 100 years ago, there were not thousands of people on cruise ships around the world or conferences bringing people from every part of the globe together.

Throughout human history, we have experienced mass deaths due to diseases. Ironically, these have been beneficial for humans as a whole.

Jared Diamond argues in “Guns, Germs, and Steel” that infectious diseases were a major reason Eursaians were able to spread their influence across the globe.

“The infectious diseases that regularly visited crowded Eurasian societies, and to which many Eurasians consequently developed immune or genetic resistance, included all of history’s most lethal killers: smallpox, measles, influenza, plague, tuberculosis, typhus, cholera, malaria, and others.”

Eurasians gained immunity through generations and generations of brutal deaths. These diseases killed swaths of the population, but they left Eurasians stronger as a whole.

“As a result, over the course of history, human populations repeatedly exposed to a particular pathogen have come to consist of a higher proportion of individuals with those genes for resistance - just because unfortunate individuals without the genes were less likely to survive to pass their genes on to babies.”

When Europeans made their way to the Americas, they brought these diseases. Native Americans had not developed immunity over the centuries. As a result, Native Americans suffered mass casualties.

While modern medicine gives us the promise of vaccines, this process takes time. The New York Times reports that a vaccine for COVID-19 will not be ready for over a year. If this is the case, there is the potential that we will have to work through this crisis with only the help of natural selection.

New generations have grown accustomed to reading about these diseases in history books. However, there is a real possibility that humankind will have to gain immunity to more diseases in its future. In a globally connected society, it will not be just the Eurasians who struggle to gain immunity.

COVID-19 will exaggerate many of the existing structures of our society. In terms of government approach and strategy, China's response to the situation is nothing short of fascinating. From a pure government control and influence stance, this type of response is unprecedented in human history. The government quarantined and shut down Wuhan, a city of 11 million people, in late January. Imagine this type of government response in the United States. Had the US government tried to quarantine a city larger than New York City, the public’s response would not be as compliant as those in Wuhan. As China’s lockdown of additional cities continues, other nations will have to prepare to replicate this quarantine model to help prevent the spread. China is in a unique position to handle this situation. The government has control over citizens and the ability to act with an iron fist in times of crisis.

This difference in governmental control is another reason to be worried about the impact on the United States and around the world. The outbreak began with just one infected person. As such, one infected person in the United States could lead to scales of outbreak similar to that of China. This is the power of exponential growth.

There are a number of additional reasons to be concerned about the impact of coronavirus. For instance, people can contract the virus and not show signs for days. Also, the virus can spread through human to human contact. AND, asymptomatic people can likely spread the virus. All of this is a recipe for a global pandemic. Until more is known of this specific virus, I will not attempt to make guesses.

In summary, a viral outbreak has the potential to wipe out large numbers of the population as supported by math and history. Stay safe and be prepared.